DIY pond maintenance vs professional service is a decision framework that compares self-managed pond care with contracted maintenance based on system complexity, biological load, risk tolerance, and accountability. The distinction is not cosmetic. It centers on how ponds function as living systems, how failure risk accumulates over time, and who is responsible for monitoring, correcting, and preventing system imbalance before damage occurs.

Most pond owners do not struggle because they ignore their ponds. They struggle because well-intended actions are applied without visibility into how filtration maturity, circulation patterns, nutrient load, and fish stress interact over time. Tasks like cleaning filters, topping off water, or treating algae may improve appearance briefly while increasing instability underneath.

The difference between DIY care and professional service shows up weeks later, not the same day. Water turns green again. Fish behavior changes. Pumps work harder. These outcomes are not caused by effort gaps. They are caused by system management gaps. Understanding where those gaps form is what determines whether a pond can be maintained safely by the owner or requires ongoing professional oversight.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat DIY Pond Maintenance Actually Involves

DIY pond maintenance is the owner-managed care of a pond system that relies on routine observation, light cleaning, and minor adjustments rather than structured monitoring or external oversight. It works only when the pond itself is simple, lightly loaded, and biologically forgiving. The responsibility for detecting problems, interpreting changes, and deciding when intervention is needed rests entirely with the owner.

At a practical level, DIY care usually includes a narrow set of tasks that keep the pond functioning day to day, but do not actively manage system risk as conditions change.

- Owner-performed cleaning and observation

This typically includes removing surface debris, rinsing skimmer baskets, checking that pumps are running, and watching fish behavior. These actions help prevent immediate blockages or visible decline, but they do not measure biological performance or system stress. According to University of Florida IFAS Extension guidance on ornamental pond care, visual clarity and surface cleanliness alone are not reliable indicators of underlying water quality stability. - Minor adjustments without structured monitoring

DIY care may involve topping off water, adjusting flow valves, or reducing feeding when algae appears. These adjustments are reactive by nature. Without regular water testing or trend tracking, changes are made based on symptoms rather than verified cause. Extension publications from Texas A&M AgriLife note that symptom-based adjustments often lag behind biological shifts in small pond systems. - No external accountability or monitoring system

In a DIY setup, there is no independent check on whether filtration capacity matches biological load, whether circulation patterns are still effective, or whether gradual imbalances are accumulating. If something drifts out of balance, there is no alert mechanism beyond visible degradation or fish stress. The system fails quietly until the owner notices. - Success depends on system simplicity

DIY maintenance tends to work only when fish load is low, filtration is uncomplicated, and seasonal swings are mild. As systems become more complex, such as higher stocking density, multiple filters, waterfalls, or warmer climates, small misjudgments compound. The first failures usually show up as recurring algae, unstable water chemistry, or equipment strain rather than sudden collapse, a pattern documented in multiple state extension pond management resources.

The key limitation of DIY pond maintenance is not effort. It is risk visibility. When the system is simple, the margin for error is wide. When it is not, DIY care lacks the feedback loops needed to prevent slow, compounding failure. For example, ammonia levels can rise gradually for days before fish show visible stress, leaving DIY owners unaware until damage has already begun.

Referenced Sources

University of Florida IFAS Extension, Ornamental Pond Maintenance and Water Quality

Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, Managing Small Pond Systems and Water Balance

What Professional Pond Maintenance Services Are Designed to Manage

Professional pond maintenance services are designed to manage ongoing system behavior, not one-time conditions. The focus is on how a pond changes over time as waste accumulates, equipment ages, seasons shift, and biological load fluctuates. Unlike DIY care, which depends on intermittent observation, professional maintenance is structured around continuous responsibility for system stability.

Professional care is built around pond maintenance as an ongoing system process, where filtration, circulation, and biological load are evaluated over time rather than reset episodically.

At a practical level, this means professionals are accountable for noticing gradual changes that are easy to miss when you only react to visible problems. A pump that is still running but moving less water, a filter that clogs faster each month, or fish behavior that subtly shifts before water quality numbers spike are all signals that point to developing imbalance rather than isolated issues.

Professional maintenance typically manages three core areas:

- Ongoing system oversight. This includes repeated inspection of flow rates, filtration performance, water clarity trends, and fish behavior across visits. The value is not any single check, but the ability to compare current conditions against prior baselines and identify drift before failure occurs.

- Biological and mechanical balance management. Professionals work to keep biological filtration, mechanical filtration, circulation, and oxygen availability functioning together. Overcorrecting one area, such as aggressively cleaning filters, is avoided because it can destabilize another. The goal is functional balance, not visual perfection.

- Preventative intervention before failure. Small adjustments are made when early warning signs appear, such as rising debris load, reduced circulation, or increased algae pressure. Addressing these early reduces the likelihood of pump burnout, biological crashes, or fish stress that require repair rather than maintenance.

This approach is consistent with system-based pond management principles outlined by organizations such as the United States Environmental Protection Agency, the University of Florida IFAS Extension, and the Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Foundation, which emphasize trend monitoring, nutrient management, and preventative system control over reactive treatment.

Professional pond maintenance is not defined by tools or products. It is defined by accountability for how the system behaves over time and by intervening early enough that problems do not compound into failures.

Pond Type and Use Case Classification

Not all ponds operate under the same constraints, even when they look similar on the surface. Pond type determines how much biological waste is produced, how dependent the system is on equipment, and how quickly imbalance becomes a real problem. This classification sits upstream of any DIY versus professional decision because it defines how much margin for error the system actually has.

At a high level, pond use cases fall into four functional categories, each with different tolerance levels and maintenance demands.

- Koi ponds carry the highest biological load. Fish produce waste continuously, which increases ammonia production and oxygen demand. Because koi ponds rely heavily on mechanical and biological filtration to process that waste, small lapses in maintenance tend to compound quickly. When filtration efficiency drops, water quality can deteriorate even if the pond still looks visually clear. Research from the University of Florida IFAS Extension shows that stocked ornamental fish ponds require consistent filtration and monitoring to prevent ammonia and nitrite accumulation that can stress or harm fish.

- Decorative ponds typically support fewer fish or none at all. With lower waste input, these systems are often more forgiving. Water quality changes tend to happen more slowly, and visual cues like debris buildup usually appear before biological stress becomes severe. According to the Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration Foundation, low stocked decorative ponds can remain stable longer with basic debris management and circulation support.

- Wildlife ponds function differently because they depend more on plants and natural processes than on mechanical equipment. Waste input fluctuates seasonally and unpredictably, but expectations for clarity and control are lower. These systems tolerate imbalance better because they are not designed around constant filtration performance. Guidance from the Royal Horticultural Society notes that wildlife ponds prioritize habitat function over controlled water chemistry.

- Commercial or HOA ponds prioritize consistency and liability control rather than flexibility. These systems are often larger, more visible, and subject to higher expectations. Equipment uptime, predictable water quality, and documented maintenance matter more than occasional visual improvement. Industry guidance from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency highlights that shared or public water features require structured monitoring because failures affect more than a single owner.

Across all pond types, the same rule applies: the higher the fish load and the greater the equipment dependency, the lower the tolerance for missed observation or delayed correction. This is why pond classification must come before deciding whether DIY care is appropriate. The system’s use case determines how much risk the owner is actually taking on when they manage it themselves.

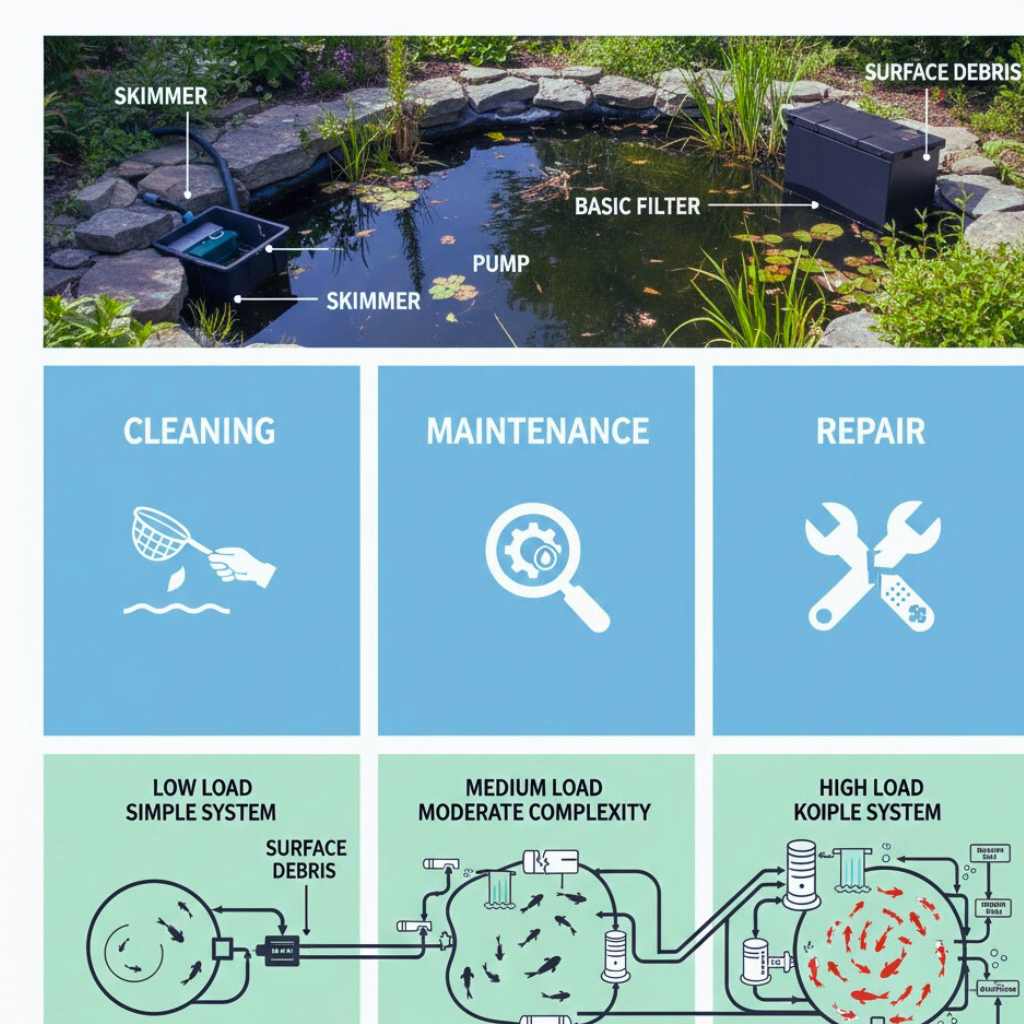

Pond Cleaning vs Pond Maintenance vs Pond Repair

People often use these terms interchangeably. That confusion is one of the main reasons ponds cycle through short improvements followed by the same problems coming back. These are not variations of the same service. They address different system states and they apply at different points in a pond’s lifecycle.

Pond cleaning addresses debris, not system behavior.

Cleaning focuses on removing physical material like leaves, sludge, and accumulated organic matter. It restores flow and improves appearance in the short term. What it does not do is correct why that debris accumulated faster than the system could process it. This distinction is central to understanding pond cleaning as a debris removal service rather than a form of ongoing system management.

Cleaning is appropriate when the underlying filtration, circulation, and biological activity are still functioning as intended.

Pond maintenance manages how the system operates over time.

Maintenance looks at how water quality, filtration, circulation, and biological load interact week after week. It involves observation, testing, and adjustment to keep those elements working together. The goal is stability, not reset. When maintenance is consistent, problems tend to surface as small shifts that can be corrected before they escalate.

Pond repair corrects failure states.

Repair becomes necessary when something has stopped functioning or can no longer perform its role. That includes failed pumps, cracked filters, leaks, collapsed plumbing, or structural breakdowns. At this stage, neither cleaning nor routine maintenance can resolve the issue because the system itself is no longer intact.

The distinction matters because each service solves a different problem. Cleaning improves conditions temporarily. Maintenance reduces the likelihood of recurring issues. Repair restores lost function after failure. When these boundaries are blurred, expectations drift and ponds get stuck reacting to symptoms instead of addressing root causes.

When the wrong service is applied to the wrong system state, ponds tend to cycle through repeat cleanings, rising costs, and delayed repairs that could have been prevented with earlier system level management.

System Load and Complexity as a Decision Factor

Some ponds become difficult to manage not because the owner is inattentive, but because the system itself crosses a threshold where small changes have outsized effects. System load and complexity determine how forgiving a pond is when something goes slightly off. Once that margin shrinks, DIY care becomes harder to sustain consistently.

In many cases, the margin for DIY care is determined early by how a pond’s original design shapes system load, including filtration sizing, circulation layout, and allowance for fish growth.

At a practical level, this comes down to three interacting pressures.

Waste production rate

As fish load increases, so does waste in the form of ammonia and organic debris. In lightly stocked ponds, the biological system can absorb short lapses in cleaning or testing. In higher load systems, waste accumulates faster than natural processes can stabilize it, which means delays or missed steps have consequences sooner rather than later.

Equipment interdependence

Simpler ponds often rely on a single pump and basic filtration. More complex systems layer mechanical filters, biological media, UV clarifiers, aeration, and sometimes multiple pumps. These components do not operate independently. A partially clogged prefilter can reduce flow, which limits biological filtration, which then affects water chemistry. Problems rarely stay isolated.

Sensitivity to imbalance

As systems grow more complex, they become less tolerant of variability. Small changes in feeding, temperature, or flow can shift oxygen availability or bacterial performance. In these conditions, the pond does not fail suddenly, but it drifts toward instability unless adjustments are made early and correctly.

At this stage, stability depends less on occasional cleaning and more on consistent monitoring, timely correction, and accountability for how the system responds over time.

This is why some ponds feel manageable for years and then quietly cross into a phase where the same level of DIY effort no longer produces the same results.

DIY Pond Maintenance vs Professional Service (Side-by-Side)

At this point, the distinction between DIY care and professional maintenance becomes easier to see when both approaches are compared across the same system demands. The table below summarizes how responsibility, risk, and correction differ once pond complexity increases.

| Decision Factor | DIY Pond Maintenance | Professional Pond Maintenance |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring responsibility | Owner observes conditions informally | Conditions are checked intentionally and repeatedly |

| Error tolerance | Higher only in simple, lightly loaded systems | Lower tolerance because deviations are detected earlier |

| Time before issues surface | Weeks or months before symptoms appear | Early indicators identified before symptoms |

| Correction window | Narrow once symptoms are visible | Wider because intervention happens earlier |

| Cost exposure | Lower upfront, higher if failures occur | More predictable through prevention |

| Risk ownership | Fully on the owner | Shared through documented oversight |

This comparison highlights that the difference is not effort, but timing and accountability. As system load increases, the cost of delayed recognition becomes more significant than the cost of ongoing oversight.

Error Tolerance and Escalation Thresholds

Some ponds are forgiving. Others are not. Error tolerance describes how much deviation a pond system can absorb before small issues escalate into larger problems. That tolerance is shaped by system load, filtration capacity, circulation design, and biological maturity.

In DIY-managed ponds, problems usually develop gradually. Missed cleanings, delayed water testing, or inconsistent feeding rarely cause immediate failure in simpler systems. Instead, the pond drifts. Flow rates decline, waste accumulates, oxygen availability fluctuates, and biological filtration efficiency slowly erodes. By the time visual symptoms appear, the underlying imbalance has often been present for weeks.

Professional maintenance operates within narrower escalation margins by design, not because the systems are more fragile, but because deviations are identified earlier. Changes like reduced pump output, rising ammonia or nitrite trends, declining dissolved oxygen, or uneven circulation patterns are addressed before they cascade into visible stress. The difference is timing and accountability, not effort.

Certain warning signals indicate when a pond is moving out of a DIY-safe range, even if no single failure has occurred yet. These indicators are observable without relying on fixed numeric targets.

- Recurring algae that returns faster after each cleaning, suggesting nutrient input exceeds system processing capacity.

- Filters clogging more frequently over time, indicating rising waste load or declining biological efficiency.

- Gradual loss of flow or circulation consistency, even after routine maintenance.

- Fish behavior changes without obvious cause, such as reduced activity or uneven distribution in the pond.

- Corrections that work for shorter periods, requiring more frequent intervention to maintain the same result.

When multiple signals appear together, error tolerance has narrowed. At that point, delayed correction becomes the primary risk rather than the original issue itself.

Once a pond crosses an escalation threshold, recovery becomes harder. Corrections take longer, risks increase, and outcomes depend more heavily on external intervention. This is why understanding a pond’s error tolerance matters. It determines whether missed steps remain manageable or quietly compound into system-level instability.

Source references:

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Water Quality Parameters

University of Florida IFAS Extension Aquatic Systems Management

North American Koi Keepers Association Water Quality Guidelines

Time-to-Failure Windows in DIY vs Professional Care

Problems in pond systems rarely appear the moment something goes off. Most ponds have a built-in buffer created by water volume, biological filtration, and existing bacterial colonies. That buffer delays visible symptoms, sometimes for weeks or months, even while stress is accumulating underneath.

In DIY care, this delay is often mistaken for stability. Water may still look clear, fish may still be feeding, and equipment may still be running. During that window, waste load can rise, flow can slowly decline, or oxygen availability can fluctuate without triggering obvious warning signs. By the time symptoms surface, the system is already correcting late rather than early.

Professional maintenance shortens this window not by reacting faster to visible problems, but by monitoring conditions that change before appearance does. Flow rates, filtration performance, oxygen movement, and biological load trends reveal imbalance earlier than clarity or algae growth. Intervention happens while the system is still compensating, not after it has fallen behind.

This difference explains why some ponds seem fine for long stretches and then deteriorate quickly. The failure is not sudden. It is delayed, cumulative, and shaped by how early the system is evaluated rather than how urgently it is treated once symptoms appear.

Source context: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency aquatic system guidance on nutrient accumulation and delayed eutrophication effects; Aquatic Eco-Systems technical literature on biological filtration response lag.

Where DIY Pond Care Commonly Breaks Down

This section focuses on failure patterns that emerge after system load, timing delays, and escalation thresholds have already narrowed the margin for DIY correction. This prevents overlap and protects extractability.

DIY pond care usually breaks down in predictable ways. Not because pond owners are careless, but because certain system behaviors are easy to miss until their effects compound. These breakdowns tend to develop quietly, and by the time they are visible, correction often requires more than routine DIY adjustments.

The critical risk is delayed recognition.

Most DIY failures are not sudden. They escalate gradually, reaching a point where biological stability, fish health, or equipment performance cannot be restored without interrupting the system more aggressively than a homeowner typically intends.

Treating symptoms instead of causes

Surface-level fixes such as skimming debris, rinsing filters, or addressing water color can temporarily improve appearance. However, when nutrient inputs from fish waste, decaying organic matter, or excess feeding remain unchanged, those symptoms return. Each cycle increases biological strain, making the system less responsive to the same corrective effort over time.

Source: University of Florida IFAS Extension – Pond Nutrient Management

Filter damage from improper cleaning

Beneficial bacteria live on filter media and pond surfaces. Over-cleaning or rinsing filters with untreated tap water reduces bacterial populations that process ammonia and nitrite. In lightly loaded systems, recovery may occur naturally. In higher-load ponds, bacterial loss can trigger prolonged instability that DIY care struggles to correct without time, testing, and controlled rebalancing.

Source: Ohio State University Extension – Biological Filtration in Ponds

Unsafe water additions

Adding untreated tap water introduces chlorine or chloramine, which can stress fish and disrupt microbial balance. Temperature differences during large top-offs can further affect dissolved oxygen levels. These changes rarely cause immediate failure, but repeated exposure compounds stress and reduces the system’s tolerance for normal fluctuations.

When these patterns overlap, the pond does not fail all at once. It enters a phase where small delays or missteps produce outsized consequences, and DIY care no longer provides enough margin to stabilize the system reliably.

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – Chlorine and Chloramine in Water

Who Is Responsible for Catching Pond Problems Early?

Pond care does not fail only because of what is done. It fails because of what is not noticed in time. Accountability and monitoring determine who is responsible for detecting drift, interpreting early signals, and deciding when correction is needed before damage accumulates.

In DIY care, responsibility rests entirely with the owner. Observation is informal and usually reactive. Changes are noticed when something looks off, smells different, or stops working the way it used to. That approach can work in simple systems, but it depends on consistency, experience, and the ability to recognize subtle biological or mechanical shifts before they compound into harder-to-reverse conditions.

DIY relies on owner awareness

Pond owners decide when to check water conditions, clean filters, or adjust feeding. There is no external checkpoint to confirm whether conditions are trending toward stability or slowly drifting. When monitoring is irregular, early warning signs such as declining flow, reduced oxygen availability, or gradual nutrient buildup often go unrecorded until the system has already moved out of its safe operating margin.

Professional maintenance changes the structure of responsibility. Monitoring is intentional rather than incidental, and corrective action is tied to documented observations rather than appearance alone.

Professional care includes tracking and follow-up

Maintenance visits typically involve repeatable checks, notes on system behavior, and follow-up decisions based on trends rather than one-off readings. The goal is not to eliminate variability, but to recognize when normal fluctuation is turning into sustained imbalance and intervene while correction still requires adjustment rather than repair.

The distinction is not effort versus laziness. It is informal awareness versus structured accountability. As systems become more complex or less forgiving, the difference between those two approaches determines whether problems are corrected early or only addressed after consequences appear.

Cost Differences Between DIY and Professional Maintenance

Cost differences between DIY and professional pond maintenance are often misunderstood because they are framed as service pricing instead of system demand. The real distinction is not whether one option costs money and the other does not. It is where time, attention, and corrective effort are spent as system load increases.

In DIY care, cost shows up primarily as time. Pond owners invest hours observing, cleaning, testing, and troubleshooting. When systems are simple, that time investment can be predictable and manageable. As system demand increases, the time required to keep conditions stable rises unevenly. Missed checks or delayed adjustments allow small issues to persist long enough to create larger corrective work later.

Professional maintenance shifts that cost into scheduled labor and repeatable oversight. Instead of absorbing time sporadically and reactively, system monitoring and adjustment are distributed across regular intervals. This does not eliminate variability or guarantee outcomes. It shortens the time between early deviation and corrective action, which limits how far problems can progress before intervention occurs.

The second cost difference appears when problems escalate. DIY care often defers cost until failure becomes visible, at which point repair, replacement, or recovery work becomes unavoidable. Professional maintenance places more cost upfront through prevention, but reduces the likelihood that minor instability turns into equipment loss, fish stress, or system disruption that is more expensive to correct later.

This tradeoff is well documented in asset management and preventative maintenance models, where routine monitoring lowers long-term failure costs by reducing delayed intervention risk (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Asset Management for Water Infrastructure).

Can Professionals Fix Problems Caused by DIY Maintenance?

Yes, many pond issues caused by DIY maintenance can be corrected if intervention happens early, but reversibility depends on how long the system has been drifting and which biological or mechanical processes have been disrupted.

Most DIY-related problems develop gradually. Nutrient accumulation, reduced oxygen transfer, declining biological filtration, or restricted flow usually build over weeks or months before visible symptoms appear. When caught during this phase, corrective maintenance can often stabilize the system by restoring circulation, protecting remaining beneficial bacteria, and reducing ongoing stressors rather than resetting the pond entirely.

However, systems left out of balance for too long lose their ability to self-correct. For example, biological filtration that has been suppressed by prolonged ammonia exposure does not recover immediately once conditions improve, even if the water looks clear. Bacterial populations take time to reestablish, and during that window the system remains vulnerable to further swings.

Delayed intervention increases cost and complexity. What begins as corrective maintenance can escalate into repair when pumps overheat from sustained restriction, filters collapse under chronic clogging, or fish health declines due to repeated stress events. At that point, recovery shifts from adjustment to reconstruction.

This is why professional involvement is less about fixing mistakes and more about timing. Early correction preserves system function. Late correction often means rebuilding what was lost, not simply restoring balance.

Source context: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, guidance on biological filtration recovery and preventative water system maintenance principles

Decision Rules for Choosing DIY or Professional Service

Choosing between DIY pond care and professional maintenance is not about preference. It is about whether the system you are managing leaves enough margin for missed signals, delayed corrections, or learning through trial and error.

Three factors consistently determine where that boundary falls.

- Pond type and system load

Ponds with low fish load, simple filtration, and minimal equipment tend to tolerate DIY care because biological demand rises slowly. As fish density increases or filtration systems become layered, waste accumulates faster and system balance depends on tighter timing and coordination. - Time availability and skill

DIY care assumes regular observation, correct interpretation of changes, and timely adjustment. When time is limited or experience is shallow, small delays compound. What could have been a minor correction often becomes a larger intervention later. - Risk tolerance

Some pond owners are comfortable monitoring trends and responding gradually. Others need predictability and lower exposure to cascading failures.

When a system’s tolerance is exceeded, it does not fail immediately. Stress accumulates quietly until correction shifts from adjustment to repair.

These decision rules are not about effort or intent. They describe how much uncertainty a pond system can absorb before consequences become structural rather than cosmetic.

When and How to Transition From DIY to Professional Care

Some ponds reach a point where the question is no longer whether DIY care is possible, but whether it remains the most stable way to manage the system. Transitioning from DIY to professional care is less about effort and more about timing. Earlier transitions tend to preserve system integrity, while delayed transitions often increase correction scope.

Early transition reduces damage

When professional oversight begins before chronic imbalance sets in, most issues remain manageable. Nutrient buildup, declining flow, or biological stress can often be corrected through adjustment rather than repair. Once instability compounds over time, interventions shift from preventative to corrective, which increases cost, disruption, and recovery time.

Baseline evaluation before ongoing care

A transition typically starts with a baseline assessment of how the pond is functioning as a system. This includes circulation behavior, filtration performance, biological load, and equipment condition. Establishing a baseline allows future changes to be evaluated against known conditions rather than guesswork. Without that reference point, ongoing adjustments risk addressing surface symptoms instead of underlying system behavior, which often leads to repeated corrections that never fully stabilize the pond.

The transition itself is not an admission of failure. It is a recognition that the system’s demands have changed. When complexity or load outpaces the margin for error, shifting to structured monitoring and intervention becomes a practical step toward restoring predictability rather than reacting to consequences after they appear.

How to Tell Which Side of the Line Your Pond Is On

After evaluating system load, error tolerance, and time-to-failure, most ponds fall into one of three practical categories.

- DIY remains workable when the pond has low fish load, simple filtration, stable circulation, and issues develop slowly enough to be noticed and corrected without urgency.

- Risk is increasing when corrections are needed more often, symptoms return faster, or system behavior changes without clear cause.

- Professional oversight becomes the safer option when delays lead to compounding effects, recovery takes longer each time, or failure consequences extend beyond appearance into fish health or equipment stress.

This framework is not about capability. It reflects how much uncertainty the system can tolerate before timing and accountability matter more than effort.

What to Do After Comparing DIY vs Professional Pond Care

Once you understand how DIY pond maintenance and professional service differ, the next step is not to react to the most recent symptom. It is to decide how much responsibility, timing risk, and uncertainty your pond system can realistically tolerate.

If your pond remains stable with simple equipment, low biological load, and slow-moving changes, continued DIY care may still be appropriate. The key condition is visibility. You need to be able to notice drift early enough that small corrections still work.

If problems are returning faster, corrections are becoming more frequent, or recovery takes longer each time, the system is signaling that its margin for error has narrowed. At that point, the question is no longer effort. It is whether delayed detection creates consequences that are harder to reverse.

Transitioning to professional care does not mean something has gone wrong. In many cases, it reflects that the pond has matured, accumulated load, or crossed a complexity threshold where structured monitoring becomes more reliable than informal observation.

The most stable next step is always the one that restores clarity about how the system is behaving now, not the one that promises the fastest visible improvement. Understanding where your pond sits today is what determines whether adjustment, monitoring, or escalation makes the most sense going forward.